Hoops, Loops, and Mallets

The Birth of 19th Century Athleisure

By Catherine Scholar, Camron-Stanford House Docent

For centuries, women were often expected to stay home or simply spectate while men indulged in outdoor and other sporting pursuits. At the end of the 19th century, women slowly started moving toward emancipation from traditional roles and behavior codes. The turn of the century saw women participating in many athletic endeavors and had specialized clothing to match: yachting, mountaineering, shooting, skating, etc.

One leisure sport, croquet, had been known in one form or another for hundreds of years, but exploded in popularity when its rules were published in 1857 by a Mr. John Jaques. In the early 1860s he began manufacturing affordable sets of wickets and mallets that could be used in home gardens and parks, and the craze took off.

This was one of the first times men and women indulged in sporting pursuits together, and in contemporary publications there was an air of naughtiness around the descriptions of croquet and other newly co-ed pastimes. Jokes conflating “croquet” with “coquette” were common, and even Harper’s Bazar declared, in 1868, that croquet was “an exquisite game, in which the stakes are soft glances and wreathing smiles, and where hearts are lost and won.”

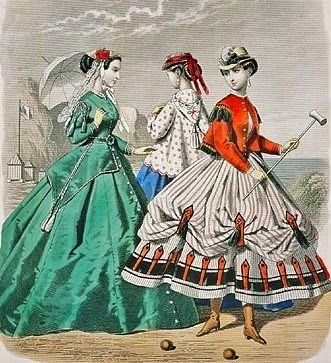

Men's clothing, of course, was no deterrent to any sport, and young girls in their shorter calf- to ankle-length skirts had no issue keeping up with the boys. Women, however, quickly found that their floor length hooped skirts were a major hindrance. Wide wire-hooped skirts moved croquet balls out of position and prevented women from wielding their mallets. At that time, women did not have dedicated sportswear; it was an unknown concept.

So what's a sporting lady to do? Get those pesky skirts out of the way, of course! Enter the skirt elevator (or dress elevator, or skirt lifter or porte-jupe if you're feeling fancy). This handy little contraption took a lot of forms, but basically what it did was loop the skirt into swags so that the hem was a few inches above the ground. Freedom!

There were many ways to raise the skirt. Some ladies sewed ribbon ties into their skirts to loop them up. Some attached "pages" to their skirts, which were shaped strips of fabric that buttoned halfway up the skirt to loop up the length. Others wore porte-jupes under their skirts, these look a bit like a 20th century garter belt, but instead of holding stockings the suspenders clip into the skirt hem. Patents exist that show how a lady could pull a cord through her dress opening to loop the skirt up while already out and dressed. In March of 1862, modiste Madame Demorest advertised "the new skirt elevator" in Godey's Lady's Book. It consisted of a yard of elastic that buttoned at the ends. Ladies were urged to button this around their waists over their clothes, so that they could pull the dress up through the elastic as needed. Yes, this was sold (10-25 cents!) AND patented.

So, once the skirt is lifted over the feet, then what? A lady can't walk around in public with her starched white petticoats showing. Immodest AND impractical, since there's no point lifting a skirt if you're still hampered by long petticoats. What developed was the Balmoral skirt, named after the British royal family's vacation home in Scotland. There, the royal ladies hiked and enjoyed the outdoors in skirts looped up over wool petticoats, a few inches shorter than usual and frequently decorated with horizontal stripes or bands of trim. These skirts were quickly adopted by sporting ladies, as they solved the cumbersome (and often soggy) cotton petticoat issue and looked fetching peeping under a looped skirt. They were usually worn over the hoop, but could also be worn without hoops. In 1858, Godey's advertised Douglas and Sherwood's patented Balmoral skirt, which combined a hoop skirt and striped woolen petticoat together. This was a luxury version; presumably most ladies simply wore a woolen petticoat over their existing hoop skirt. There are numerous extant photos of 1860s ladies skating, mountaineering, shooting, and hiking in wool Balmoral skirts with looped dresses over them.

Working women also embraced the practical petticoats; in 1866, Millie Trevallee, a kitchen worker in a boarding hall at Michigan State University, spent $5.75 on a Balmoral skirt. Given that she was earning $2-2.50 a week, the petticoat was clearly a highly desired garment. A wool petticoat was more practical than a hoopskirt in a kitchen, and safer around open fires.

Travelling women also found the Balmoral skirt indispensable. In Anne Bowman’s 1864 novel The Young Yachtsmen, or, the Wreck of the Gipsy, a young lady is advised to wear Balmoral skirts on board ship: “… one dress for the voyage, which is to be dark tweed; with Balmoral petticoats.” Her practical mother recognizes immediately that wearing a hoopskirt on a windy ship’s deck is nearly impossible, and unavoidably immodest.

Before long, fashion grabbed hold of these practical sporting styles. First you saw ladies' magazines advocating the use of dress elevators during wet and muddy weather. In 1864 Godey's advocated the wearing of "Summer Balmorals" made of muslin or twilled cotton... all the convenience of looped skirts, none of the warmth of wool. Fashion plates soon showed looped skirts over fancy underskirts for all kinds of occasions, not just sporting endeavors.

The style burned itself out by the end of the 1860s. Balmoral petticoats, in all their practical glory, were embraced by older ladies and women doing physical labor, both enslaved and free. Fashionable women turned their roving eyes to the new bustled styles of the 1870s. By 1867 the Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine was advocating jeweled dress elevators “only fit to wear in a drawing-room”. The practical beginnings of the style were clearly over when the dress elevator became an eveningwear accessory.

The spirit of sportswear, however, lived on. After the croquet craze came the lawn tennis trend, (in corsets and bustles!) and by the turn of the century women were participating in nearly every sport that men enjoyed, and there was a jaunty outfit recommended for each sport. Women that could afford such specialized clothing wore them all!

By the end of the century, the “New Woman” was emerging. This woman was educated, adventuresome, and very likely to pursue a career, at least until she married. She embraced practical, mens-wear inspired clothing for her adventures, and discovered the concept of clothing separates instead of dresses. Practical and non-restricting clothing was required by women of all classes as they began their pilgrimage out of the home. Sportswear and separates fit the bill perfectly.

By 1920 our New Woman was showing her legs and winning the vote. You might say it all began with croquet!

Catherine Scholar read “Little House on the Prairie" at age five and has been obsessed with historic clothing ever since. She learned to sew at her mother's knee and to embroider at her grandmother's. In high school she discovered vintage dance, the Northern Renaissance Pleasure Faire, and Dickens Fair, and was amazed to learn that she could combine her passions for dance, costume, history and theater. Catherine served on the board of the Greater Bay Area Costumers Guild for 10 years as Newsletter Editor, Events Coordinator, and President. She has taught many costuming workshops for GBACG, Lacis, Renaissance Fabrics, 1886/Costume On, Costume Skills Institute, and Costume College. She is a docent at Camron-Stanford House.